Pink Floyd weren’t the first to use a prism to split light into a rainbow; all the credit goes to Isaac Newton there. Newton discovered that if sunlight goes through a prism, the white light splits up into the delightful spectrum that colours the world around us: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet and everything in between. These colours are all just different wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, more specifically the visible part which ranges from 700 nanometres (you might know it better as red) to 400 nanometres (violet). For example, lime green corresponds to a wavelength of about 550 nanometres (but lime green sounds a bit more artistic). When light passes through a material it is “refracted”, which essentially means the light slows down a little as it travels through denser material making objects appear to shift – try sticking a pencil in a glass of water to see this effect. However, the amount by which the light refracts depends on its wavelength, so all the different colours of light refract by a different amount and split up – this is what gives us the album cover of The Dark Side of the Moon.

Rainbows

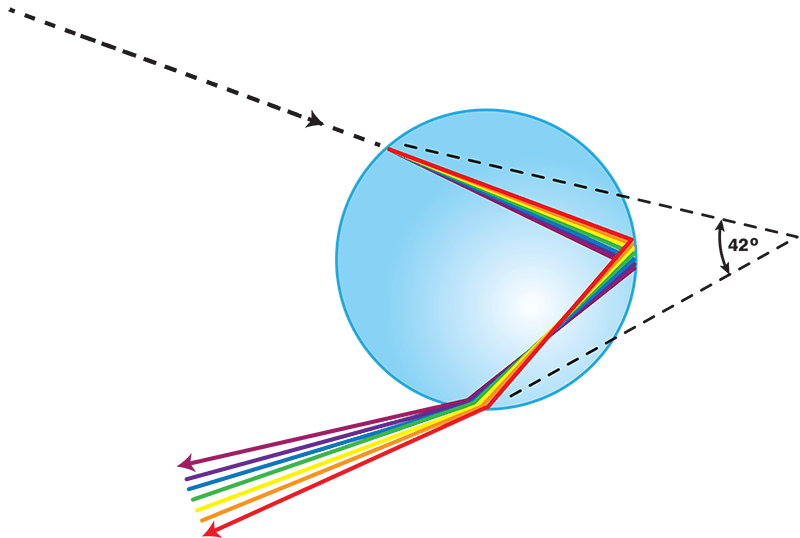

The atmosphere around us is full of water droplets, especially after it has rained and all these little water droplets act like tiny little prisms and split the light. Sunlight enters the water droplet and refracts, splitting into the different colours, then reflects off the back of the droplet and comes back out. This is why you can only see a rainbow if the Sun is behind you. You can also only see a rainbow if the angle between the Sun, water droplets and you is just right – that Goldilocks angle is 42 degrees – because light always reflects off the inside of the water droplet at that angle.

Since the position of a rainbow depends on that angle, it means that the rainbow you see is different to the one anyone else sees and if you try to move towards the rainbow, it will move away and you’ll never be able to reach it. A rainbow isn’t a physical thing, it’s really just an optical illusion. Good luck finding that pot of gold.

Blue Skies & Orange Sunsets

Our atmosphere is great; not only does it keep us warm it also gives us our Instagram-worthy skies. The atmosphere is made up of billions of tiny molecules of nitrogen and oxygen among other things. When light from the Sun reaches the atmosphere it bumps into all these molecules in a process known as ‘scattering’. Because the wavelength of visible light is much larger than the size of these molecules, a particular kind of scattering occurs called ‘Rayleigh scattering’* where light of shorter wavelengths, such as blue, is scattered much more efficiently. So violet and blue light are scattered very quickly and spread out all over the sky but the orange and red light with their long wavelengths meander very slowly. (Note: the reason the sky isn’t purple is that the cones in our eyes are more sensitive to blue than purple – but we’re starting to poach on biology’s turf here.)

So in a nutshell why is the sky blue? Because of our atmosphere. That’s why the sky above the Moon is pitch black, because it has a negligible atmosphere. But then why does the sky change colour at sunrise and sunset?

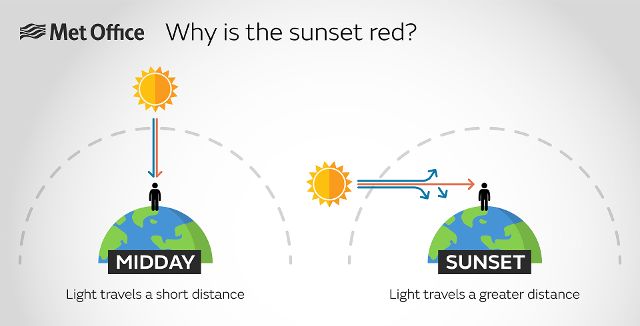

What we haven’t taken into account yet is the angle at which sunlight is incident on the Earth’s surface and as a consequence how much of the atmosphere the light has to go through. The atmosphere can be thought of as a ring around the Earth so when the Sun is directly overhead, light only has to travel a short distance to reach the surface (or more specifically your eyes). However, if the Sun is at an angle the light has to travel longer and longer distances up until the longest distance which is when the Sun is rising or setting on the horizon.

This distance has a huge impact on the colour of the sky – as we established, blue light will get scattered the most as sunlight filters through the atmosphere. When the Sun is directly overhead, light travels in a straight line downwards and over that short distance barely any light will be scattered – that’s why the sky appears almost white at noon and when you look directly at the Sun (not recommended). However, as the Sun goes down in the sky its light travels a longer distance through the atmosphere so more of the blue light will get scattered away from our line of sight until we can only see the remaining yellow, orange and red light heading towards us.

You can see a great example of this if you ever have the chance to view a sunset from an airplane or if you’re feeling particularly adventurous, the International Space Station. You can see all the different layers of colours from black space (where there’s no atmosphere to scatter light), to the blue sky (where the light travels through only a thin piece of atmosphere and scatters a little), to the red and orange hues close to the horizon (where the sunlight has travelled far enough for all the blue light to have scattered away). It’s not a bad view.

* Note that this whole discussion applies only to clear skies. When it’s cloudy, a different scattering mechanism occurs called Mie scattering, as the molecules that make up clouds are on a similar size scale to the wavelength of incoming light. Contrary to Rayleigh scattering where the amount of scattering depends strongly on wavelength, Mie scattering does not depend on wavelength, so all visible light is scattered by the same amount. The combination of all colours creates white light, so clouds look white.